Don’t Feed the Monkey Mind – How Educators can Support Anxious Students

Students with Learning Disabilities and ADHD often experience increased anxiety at school. School is a central part of their lives, and they often feel the extra weight of trying to be successful due to their learning challenges. Confronting regular academic and social challenges can further diminish their self-efficacy and confidence, which, in turn, can lead to increased anxiety levels. A small degree of anxiety is good and helps students to be motivated and perform better at school. However, when anxiety becomes overwhelming, it is a problem and can interfere with a students’ well-being and performance. While parents play a crucial role in building up resilience in their anxious children (see Moving From Enabling to Challenging Anxiety: Addressing Accommodation - Foothills Academy), teachers and educators can also contribute significantly by creating a classroom environment where students can learn to break free from anxiety.

In supporting students with anxiety, the first crucial step for teachers is to recognize signs of anxiety. Given that anxiety is often internalized, identifying anxiety-driven behaviors can be challenging. In the classroom, students with anxiety may exhibit a range of behaviors, including:

- Difficulties listening to and remembering instructions because the mind is occupied with worries.

- Refusing to participate in activities or showing negative emotional reactions in response to an anxiety-provoking task.

- Missing school.

- Frequent asking for reassurance.

- Being overly perfectionistic.

- Avoiding socializing.

- Complaining about aches and pains when faced with a challenge.

After recognizing how a student’s anxiety impacts them in class, teachers and educators are faced with a difficult task when it comes to managing a student’s anxiety. They may find themselves spending a lot of time reassuring the student, managing their emotional reactions, or trying to compensate for frequent absenteeism. It can be very easy to accommodate a students’ anxiety rather than challenge them to face their fears. With the best intentions, teachers often use strategies that provide temporary relief to the anxious student. However, these strategies ultimately reinforce anxiety and allow it to linger.

Some ways in which teachers may be accommodating for anxiety include:

- Providing Escapes: Allowing a student to leave the classroom whenever they feel anxious reinforces avoidance behaviors and keeps the student from learning to cope with their anxiety. The same is true for allowing a student to doodle or play a board game instead of doing the activity that makes them anxious.

- Continuous reassurance: Telling a student that they will be ‘fine’ and don’t need to worry can make the student reliant on frequent validation from the teacher. Consequently, they may struggle to develop confidence in their ability to handle difficulties.

- Reducing Expectations: Lowering academic or behavioral expectations for the anxious student such as giving them the answers to a problem can keep them from engaging in problem-solving themselves.

- Avoiding Trigger Topics: While sensitivity is important, completely avoiding topics or assignments that make the student anxious might prevent them from developing resilience and coping strategies.

- Overemphasis on Anxiety: Constantly checking in with a student about their anxiety can amplify their feelings of anxiety. It's important to provide support but not over-focus on their anxiety.

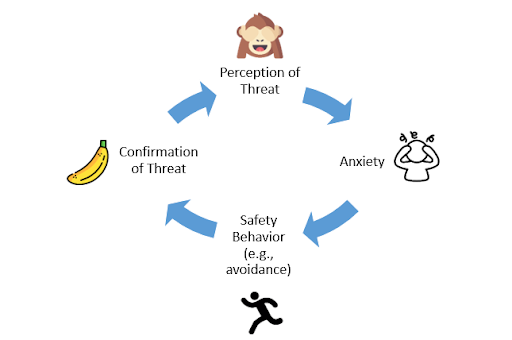

In order to switch our approach towards students with anxiety, it's essential to recognize how anxiety can become ingrained in their daily experiences. By understanding the cycle of anxiety, educators can help students build resilience, rather than perpetuate their anxiety through well-intentioned but counterproductive accommodations.

The Anxiety Monkey

Psychologist Dr. Jennifer Shannon offers a helpful analogy to understand the cycle of anxiety in a student by comparing anxiety to a monkey. Imagine there's a metaphorical anxious monkey in the student’s mind. This monkey's job is to keep the student safe, but it doesn't quite understand the difference between real dangers and normal everyday challenges. Let's say you ask the student to give a presentation in front of the class. The anxious monkey starts to worry. It asks, "What if we mess up, and get a bad grade? What if we drop our notes and everyone starts laughing?" The monkey's favorite questions always begin with "What if...?" It doesn't want the student to give the presentation, so it sounds the alarm. As a result, the student starts feeling dizzy, and their stomach hurts. If the teacher now allows the student to avoid the presentation and be sent home, the anxious monkey feels like it did a good job. It thinks, "I knew this was dangerous, and I saved you from embarrassment. You need me."

Dr. Shannon compares giving in to anxiety to feeding the monkey a banana. The problem with feeding the monkey is that it becomes stronger, louder, and more anxious every time it is fed. The only way to break the cycle of anxiety is to teach the monkey that it was wrong to sound the alarm and that the student is able to face the challenge.

How to move away from feeding the monkey

What can teachers and educators do to help students break out of the cycle of anxiety and avoid feeding the monkey bananas? First, teachers may choose to talk with their students about anxiety using the monkey analogy. This can help students to comprehend their own feelings of anxiety and understand why their teacher is no longer letting them avoid anxiety provoking activities. Teaching a student to cope with their fears will also be more successful if the students’ parents are on board and agree to a plan of no longer accommodating anxiety.

Classroom strategies to challenge the monkey mind involve:

- Identify the “monkey mind”: Help the student to recognize when their feelings are caused by the anxiety monkey. When a student expresses fears, you may ask them “I understand that you feel anxious but I wonder if that is your anxiety monkey talking. Let’s think of a way we can teach the monkey mind that you are able to face this challenge”.

- Use coping strategies: Teach the student simple breathing or relaxation techniques to manage acute anxiety.

- Modeling: Demonstrate how to handle stress and anxiety in a constructive way. Share personal experiences of overcoming challenges and managing anxiety effectively.

- Gradual exposure and achievable goals: Gradually introduce the source of anxiety in a controlled and supportive manner. Start with smaller, less anxiety-provoking tasks and gradually increase the challenge over time. Work with the student to set specific, achievable goals.

- Rewards and praise: Celebrate the student's successes and milestones in managing anxiety. Acknowledge their efforts and resilience.

In summary, teachers and educators face the challenging task of helping anxious students break free from the cycle of anxiety without inadvertently reinforcing avoidance behaviors. To move away from accommodating anxiety and help students confront their fears, teachers can use the monkey analogy to help students understand their anxiety. Additionally, they can help the student to use coping strategies and gradually expose students to their fears. This is no easy task. When students are encouraged to confront their anxieties, it's natural to expect some resistance, particularly if they have grown accustomed to a supportive environment that eliminates stress and accommodates their anxiety. However, teachers and educators can play a vital role in helping students build the skills to manage their anxiety effectively and thrive in the face of challenges.

Additional Resources:

- “Don't Feed the Monkey Mind: How to Stop the Cycle of Anxiety, Fear, and Worry” by Dr. Jennifer Shannon

- “Anxious Kids, Anxious Parents: 7 Ways to Stop the Worry Cycle and Raise Courageous and Independent Children” by Lynn Lyons and Reid Wilson